Crypto Commons 2020 review and v1.0 changelog

It has been just over one year since I released version 0.8 of Peer Production on the Crypto Commons (PPCC), so this change log for the upgrade from version 0.8 to 1.0 is doubling as a recap of 2020.

If you haven’t read PPCC most of the material here is integrated within it somewhere, along with a general introduction to open source, peer production, and common pool resources - and an exploration of how these concepts feature in decentralized cryptocurrency ecosystems.

You can see the full changelog in the Pull Request to merge version 1.0 changes. One big change throughout the resource is proper referencing (with footnotes) instead of just the links in the text, I hope someone appreciates those!

FLOSS on the ropes

Nadia Eghbal’s new book, Working in Public: The Making and Maintenance of Open Source Software 1, came out this year, and it’s great. It updates the survey of open source software production in the excellent Roads and Bridges 2, which is free to access and referenced heavily by PPCC, and provides a much more general introduction to open source development. I was happy to see the scope expand from Roads and Bridges to incorporate Commons Based Peer Production and the governance of common pool resources, the work of Benkler and Ostrom featuring heavily, and it even considers intrinsic and extrinsic motivation as well! The book also benefits greatly from Nadia’s time at GitHub, with reams of interesting stats about how the platform is being used by open source communities. I heartily recommend this book for anyone with an interest in how contemporary open source infrastructure is created and maintained.

One of the trends Nadia’s work highlights is the decline in prominence of the FLOSS (Free Libre Open Source Software) ethos, which is quite anti-corporate, in favour of a more apolitical adoption of Open Source as a generic best practice for software development. The dominant role corporations have come to play in some domains of OSS is making it clearer who the primary beneficiaries are, economically at least, and this is giving some contributors cause to pause and consider where it’s all headed 3. Mozilla has been a major player in open source, offering the most viable alternative web browser to the more surveillance-friendly android backed by Google and co., but had to lay off 4 250 workers this year due to “coronavirus-era revenue declines”.

The general sense seems to be that the Free Software movement has been dead for a while, with the GNU GPLv3 licensing debate 5 and outcome back in 2007 looking like a pivotal moment in its decline. In 2007, some advocates of Free Software wanted to prevent the “Tivoization” of FOSS, where hardware manufacturers could use it within products that restricted the freedom of users to further modify that hardware and software after buying it through forms of imposed lock-in. The GPLv3 license in 2015 accounted for just 8.88% of GitHub repositories6, lower than GPLv2 (13%), with GPL now less commonly used than the more permissive MIT license.

It seems that there is growing disillusionment now with the state of the Open Source commons. After becoming more friendly to corporate interests much of the OS ecosystem is being colonised by those interests, and many contributors are feeling like their work is exposed - to be picked up by companies whose adoption will generate a lot of work for the project, but probably little revenue.

Intrinsic motivation usually covers the creation of code because coders like to make new things, but maintenance is another story. Now we have come to depend on open source software for much of our communications, but there has been a lack of consideration paid to the web of dependencies underpinning many popular web applications, and the people who keep all of those packages and libraries working and secure.

Crypto Commons funding strong

Open Source software supporting public blockchains is an exception to the general trend of decline, while some projects have struggled during an extended bear market others have seen their funding situation improve.

Bitcoin’s situation with regard to the funding of core developers has improved considerably in recent years, and in 2020 many new funding schemes were announced. The year also saw some great reeporting and commentary on Bitcoin development funding:

2020-02-18 7: Nice infographic from Bitcoin Magazine which names funded developers and notes funding relations.

2020-03-28 8: BitMEX Research compiled a list of 17 organizations funding Bitcoin research and development, defined broadly to include projects like Lightning Network. Entities funding the most developers are Blockstream, Lightning Labs, Square Crypto (mix of in-house LN devs and sponsoring Bitcoin Core devs), MIT Digital Currency Initiative and Chaincode fund 6-8 developers each.

2020-08-06 9: This piece by Nic Carter hails Bitcoin’s Patronage system as an unheralded strength, and celebrates the significant improvement which has occurred in the last few years, during which time funding has expanded beyond Blockstream and MIT to encompass a wider range of patrons, and also funding of projects beyond Bitcoin Core. The message that Bitcoin development needs funding for Bitcoin to succeed is reaching the entities who benefit from Bitcoin and seek to build it into their businesses - it is their responsibility, and more of them are now stepping up. The article also criticises projects with dedicated funding for development from the blockchain, and in many cases those criticisms are valid.

When it comes to decentralization, blockchains which have a dominant corporate entity are inferior to those without such an entity calling the shots. Patronage by the companies which rely on Bitcoin is better than a single ICO or block reward funded company dominating development, but I think it’s setting one’s sights too low to suggest that it’s the best possible way to fund development of the crypto commons. I’m less sceptical of the role for this kind of patronage now than I was 2 years ago, now that it’s happening at a more reasonable scale - but I think we need to see how it goes over the next few years as all of the recently announced or implemented funding streams develop and interact.

Monero’s Community Crowdfunding System (CCS) is also still going strong, and in a show of strength was able to source 200 XMR (~$26,000) for a researcher (Sarang) who had been working on the project for 6 years (3 full-time) to take some paid time off, after that researcher had announced they would be stepping away from work on the project to take a break and did not intend to return. In Monero’s CCS the Core developers approve proposals which they feel have merit and these are open for donations from the community.

Decred’s Treasury is also still going strong and barely touched its impressive savings of ~660,000 DCR despite a year where the exchange rate for DCR/USD was quite low for extended periods. Over the year this has funded developers to work on repositories ranging from the full node dcrd to the dcrdata block explorer, dcrdex decentralized exchange, mobile wallets, voting service providers, etc. Anecdotally based on observation of the proposal discussions, I would say the lower exchange rate has affected stakeholder sentiment about spending this DCR, but as I found in my review of the second year of Politeia 10 proposals, there is still a strong trend whereby established contractors’ proposals are more often than not approved. With the forthcoming v1.6 release, stakeholders will vote to change the consensus rules (as detailed in DCP-006) to decentralize the process of spending from the Decred Treasury - monthly payments to contractors will require stakeholder support in an on chain vote.

Once v1.6 is released and enough PoW miners and PoS voters have upgraded, an on chain voting process will take place to activate the new rules. These changes require approval from 75% of the tickets called to vote in a ~21 day interval. This vote is expected to pass easily because the broad outline of work to decentralize the Treasury was funded by a Politeia proposal which had 97.5% approval.

In 2020 Politeia, Decred’s proposal discussion and voting platform, has been extended and in particular the contractor management system has progressed a long way. All of the Decred contractors use this to submit invoices and get paid, it is also being equipped with tools to help review the work of contractors. Politeia gives users cryptographic identities and they sign their contributions (proposals and comments) and these are all hashed and stored in the Decred chain, with the end result being that it’s not possible to change the historical record, it benefits from blockchain anchoring without bloating the chain.

There are some other projects which host documents associated with proposals on IPFS, but I’m surprised by how often I still see links to Dropbox or Google docs to find the definitive version of some proposal, and at how the key discussion space is often a standard forum. These platforms are all vulnerable to key documents disappearing or being edited without a good audit trail.

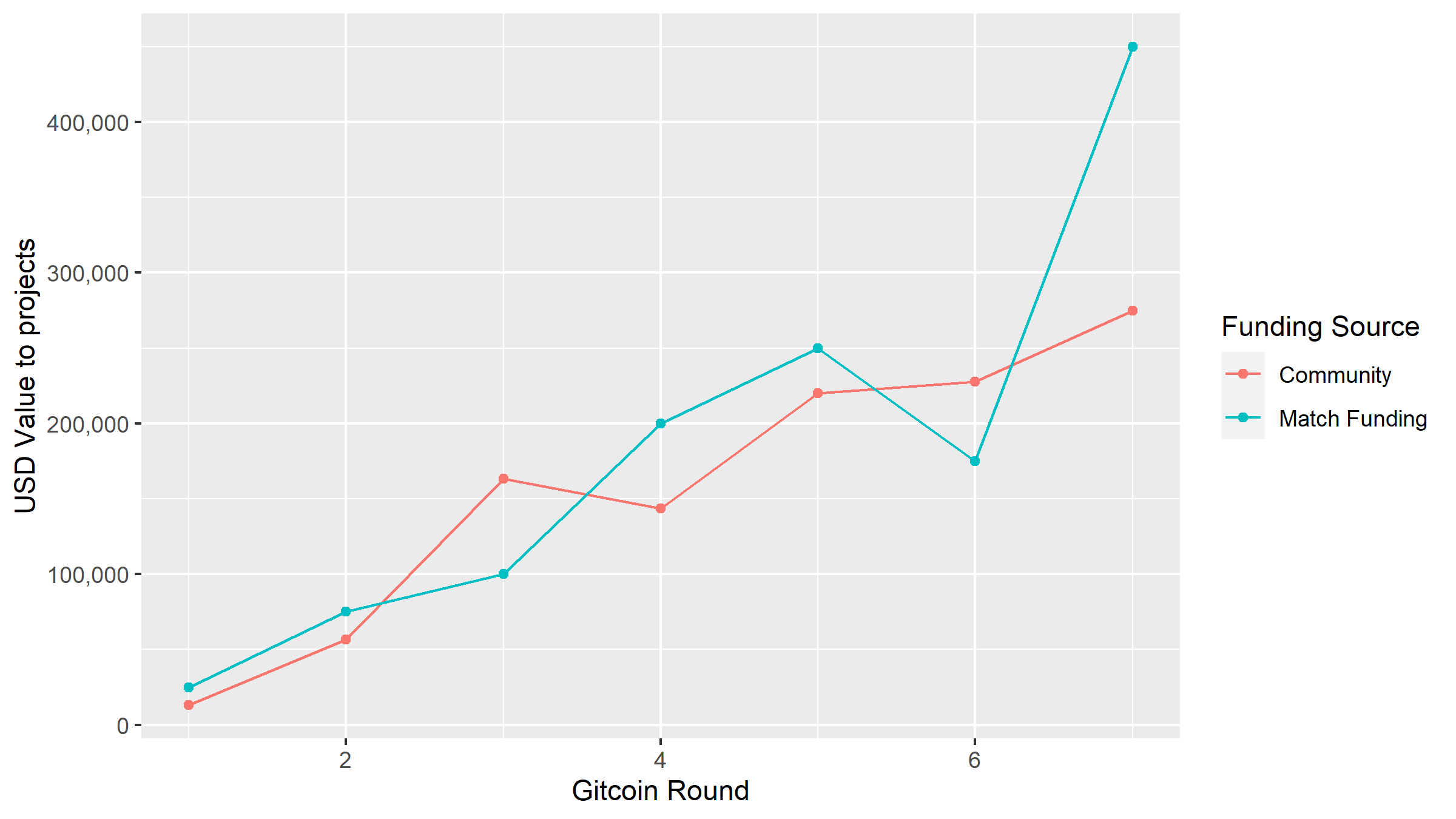

Gitcoin has come on a long way in 2020, running a further 4 quadratic funding rounds which reached new scale in terms of the level of matching and contributed funding.

Gitcoin funding per round by source

Gitcoin also expanded its remit by incorporating $100K matching funds for a one-off Public Health fund in round 5 11, and $50K matching funds for Crypto for Black Lives projects in round 6 12. In round 7 the range of funders expanded considerably to include a number of DeFi projects and people, since then Kraken has also joined with $150K of matching funds. This higher level of backing is allowing the Gitcoin team to sustain its ongoing costs of $250K per quarter for development and puts the project on a more secure footing financially. This had previously been an unknown, and Gitcoin co-founder Kevin Owocki had opened an EIP (1789) which proposed that inflation funding (20% of issuance) be allocated to Ethereum “ecosystem stewardship”.

Gitcoin also extended its scope beyond Ethereum recently with the first Zcash Gitcoin Grants 13 round, where $25K matching funds were distributed on the basis of 156 donations totalling $2,137. This was the first Gitcoin grant round on a UTXO chain and furthermore many Zcash users expressed a desire to be able to use shielded transactions to donate/receive, which were not supported for this initial round.

The major controversy around Gitcoin in 2020 concerned the share of funding which was going to popular social media personalities in the Ecosystem, specifically @antiprosynth. This was addressed by Vitalik Buterin in his results commentary post for round 4 14. @antiprosynth is a twitter account that tweets pro-Ethereum messaging and information, and was at one point on course to be the largest beneficiary in a new “Media” category and receive a ~$20K match in funding, which caused some discussion of whether this was too much for tweeting or whether tweeting was even a public good. By the end antiprosynth’s matching amount had reduced to $11,316, after a campaign to increase contributions to causes deemed more worthy had seen a couple of those overtake it.

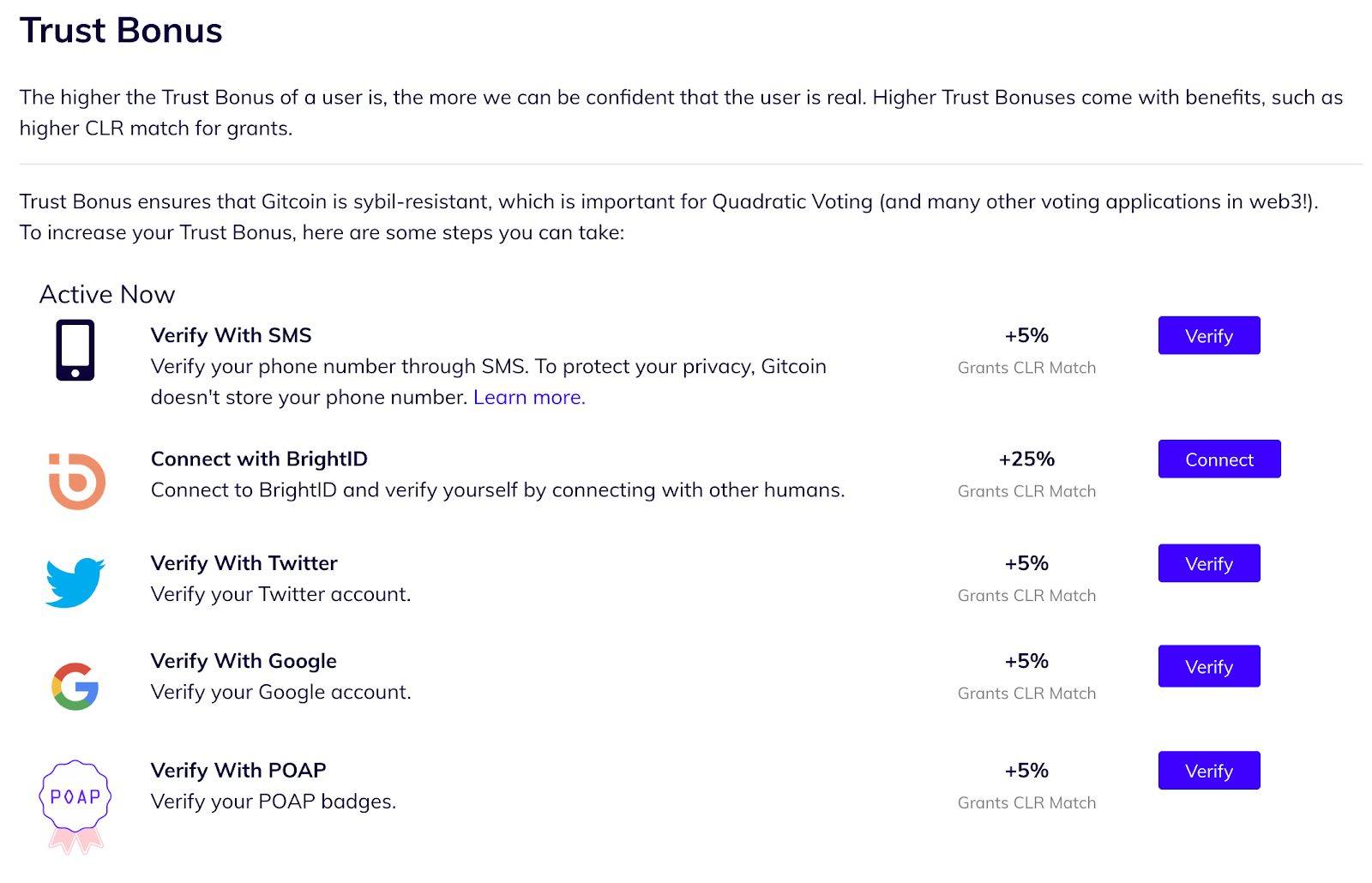

Gitcoin is meeting a need in the Ethereum ecosystem, as evidenced by the funding which major institutions like the Ethereum Foundation have poured into it. It is an interesting experiment in quadratic funding, which encourages smaller stakeholders to participate by matching their contribution with a relatively larger share than those who donate a lot. The major problem with applying quadratic funding in the crypto space is that it’s usually easy for a motivated actor to cheat by creating multiple accounts and spreading their funds out that way, to avoid the penalty imposed on larger contributors by appearing as many smaller contributors, to get the benefits which these participants receive. This is the same issue which limits the utility of open decentralized systems which are “one person one vote”, it doesn’t work because people can create as many “persons” as they want, unless there is some central authority to decide what counts as a person (in this case the Gitcoin team).

There have indeed been some issues with gaming the system as recounted in Vitalik’s blog posts, and as a way to compensate there are now a series of methods through which a funder can enhance their matching level or “Trust Bonus”. I haven’t looked into the privacy implications of completing any or a number of these and associating that identifying information with one’s Ethereum account address, but I hope the people who get the “Trust Bonus” have done their research and that they’re not trusting Gitcoin with too much sensitive info.

Gitcoin Trust Bonus

There is a further section below about DAOs, in particular Moloch DAOs, which are relevant to Ethereum funding.

Social Tokens, Crypto-gated Communities

One of the emerging trends of 2020 has been “Social Tokens”, where people issue their own tokens for various purposes, some of which seem to border on securitizing the self. Colin Harper has written about how personal tokens raise red flags 15, and those are all valid concerns, but as he notes they do not seem to be preventing many people from launching this kind of token.

Some examples:

Frenchman Alex Masmej, 23 years old, recently raised $20,000 on Ethereum by tokenizing himself. Now he wants his investors to vote on his life choices - Coindesk 16

FC Barcelona’s Token Sale Hit $1.3M Cap in Under 2 Hours - Coindesk 17

Lil Pump Is Doing a Social Token Called PumpCoin - Coindesk 18

Rapper Lil Yachty Sells Out Social Token in 21 Minutes - Coindesk 19

When established entities with large followings like Barcelona FC start experimenting with using tokens to promote engagement, it starts to seem likely that this kind of token will be the first contact many people have with blockchain technology.

There’s an app (tryroll) which allows anyone to easily mint their own tokens and suggests they start offering services in exchange for these tokens.

There’s a platform (fyooz) which invites readers to “Become a token”, complete with big flashy image promoting the concept to “Monetize Your Fame”, there may be some brainwashing attempt going on there so be careful not to get sucked in. At fyooz, token generation is a more bespoke affair and is more for people with fame to monetize, like Lil Yachty.

I haven’t seen any usage stats for tryroll yet, it could explode in 2021 and there could be hundreds of thousands of these “currencies”, but that seems fairly impractical to me, so it’s also possible the whole thing fizzles out. Should be a fun one to watch next year.

A new and interesting trend I noticed in relation to “Social tokens” is the private Telegram channel which requires a balance in some token to access. Private groups and “paid groups” are not new of course, and are notoriously the domain of con artists, but the token-secured Telegram chats are an interesting development that seems to be working for some communities. “Access” is one thing that anyone can sell, and there are tools now which can tie that access to a token, thus providing a practical feature of that token which can be delivered in an observable and ongoing way. In the process this kind of barrier can make community management much easier as it makes the group less accessible to casual trolls and attaches a real cost to an account.

These private channels seem to be central to the appeal of a number of social tokens in this optimistic overview 20, along with promises about shares and airdrops which are probably not binding in any meaningful way.

Restricted access to a discussion channel is also part of the premium offering for popular DeFi news source The Defiant, and I guess we’re going to see this kind of pay for access media more and more, in the crypto space and beyond. The ad-supported journalism model is tough, so people are keen to move away from it, and a “freemium” model with some public offering and more for a fee is popular in other domains, like gaming. In this case the common pool resource is attention of people who understand the technology and what’s happening on the networks, people value hearing their informed perspective early and using this information to make better trading decisions and get in early to new projects.

One of the drivers of much analysis and reporting in the cryptocurrency space is edge. People value information that allows them to understand market phenomena better or faster than other participants and make the right moves at the most advantageous times. This kind of information can often fetch a good rate in the market when sold as a club good.

Any kind of paywall is however creating a huge barrier to many people who could otherwise benefit from an information resource. Levelling the playing field is one of the crypto aspirations I like, it’s good that more people can learn about this stuff more quickly and that they don’t have to invest money up front in resources to help them. There would be something sadly ironic about a crypto commons that is publicly recorded and accessible through distributed ledgers, but where the best accounts of what’s going on and how it works are behind paywalls.

Decentralized Finance

DeFi has been driving a lot of the news, social media and market activity this year, with a number of Ethereum-based decentralized exchange and lending protocols gaining significant traction. One of the top memes here was yield farming, finding ways to deploy capital assets in a way which would generate attractive yields - often involving stringing a number of different protocol transactions together (composability).

The Defi Pulse site is good for getting a quick sense of what’s hot in the DeFi space, with “total value locked”, the capital deployed with a platform, taken as a key measure of success. DeFi markets are driven by people “locking” an asset that has value in a way that allows them to derive a yield from it. The key assets being locked are ETH (as Maker DAI stablecoin), Bitcoin (as WBTC, renBTC) and other Ethereum-based tokens - the tokens issued on the basis of this collateral are the fuel which powers the DeFi ecosystem.

DeFi Foundations

The process of locking a crypto-asset to obtain something is not risk-free, and each of these services presents a different kind of risk. These warrant a mention, because the stablecoins and wrapped assets are also foundational for the rest of DeFi. Most of the methods involve relying on some centralized custodian to perform minting/burning functions and track the balances, like Tether (backed by a company), WBTC (backed by a consortium of companies), renBTC (backed by a multi-sig). In these cases the assets are as secure or robust as the backing entity, and most of them have ways in which transactions and balances can be selectively censored/nullified.

MakerDAO and the DAI asset take a different approach which aims to be more decentralized by removing the centralized custody of assets from the equation. Instead, collateral (initially ETH, now any of a basket of Ethereum-based tokens) is locked up in an on chain transaction, allowing a certain amount of DAI to be minted. The rate at which the DAI is backed, and associated fees, can be controlled by Maker token holders in the form of executive votes to approve changes to the protocol. Rate changes offer certain levers that can be pulled to try and encourage the DAI price to behave as desired (stability at 1 DAI = 1 USD), but this cannot be forced by the system. There have also been issues where the system behaved in unexpected and problematic ways while under strain, such as the “Black Thursday“21 event in March 2020 when $8.3 million of collateralized ETH was “sold” for nothing in auctions that didn’t have any bids, leading to losses for some users which are still being litigated 22after MKR holders voted 23 to not compensate these users. This dispute is an interesting one to watch as it sets expectations for how the MKR and DAI stakeholders will interact when the platform has a technical issue which impacts users financially.

Maker’s DAI has a very different risk profile to the centralized stable-assets, it lacks some of the failure modes of older assets like Tether, but as with any system that derives strength from decentralization, it’s important to ask how decentralized Maker’s governance is. Key factors here are relatively concentrated MKR balances, such that relatively few people are needed to form a majority of voting power, and votes typically have around 40 participants total. There are also major roles for the Maker Foundation and a risk team, who prepare the proposals that MKR holders will approve. Originally Maker Foundation members had an executive shutdown key which could be used to halt the system and liquidate collateral, should something go catastrophically wrong. This has been disabled, and triggering the emergency shutdown now requires 50,000 MKR to be deposited to a contract address.

Although the absolute number of participants is not large, the Maker DAO members are making extensive use of the polling and executive votes - 355 polls have been completed and many executive votes (mostly adjusting fees) in the ~15 months since it was adopted in August 2019. The executive votes run continuously, and are constructed by the risk team, which itself has polling proposals to establish support for its actions. This is at least an impressively comprehensive record of the actions taken in the governance of DAI.

MakerDAO is taking on challenges which are non-trivial to address, the system has exhibited some undesired behavior but it is probably the most or only decentralized stablecoin and has been widely adopted within the Ethereum ecosystem. This is a great success for Maker, and establishes it as important within the ecosystem, which should give it some clout in Ethereum’s governance.

In late October 2020 flash loans became another thing for Maker’s governors to worry about, as BProtocol flash-borrowed 13,000 MKR to vote for their own proposal. In this case they were already winning and just speeded the process along, so no harm done, but it still prompted a discussion of how to disincentivize MKR holders from leaving their MKR in a liquidity pool where it can be used to attack the project, until such times as this attack vector can be addressed.

Yield Farming Mania

The point at which I personally realized I could no longer ignore DeFi was when YAM appeared24 on the scene and became wildly popular (and profitable) for a brief few days, before turning into the subject of a successful last-ditch community mobilization effort, which then failed because of a second unforeseen critical issue. I found it funny, and also intriguing, that something which was billed as a “governance token” could acquire so much (notional) value so quickly, despite being so bad at what it was aiming to do - the system was set up so that all the funding would become un-spendable within days, the dev fund turning into a black hole that swallowed the whole project.25 All of this happened within the space of about 3 days. Yam was pitched as a monetary experiment, it mashed up aspects of some popular DeFi protocols to produce an “elastic supply cryptocurrency, which expands and contracts supply in response to market conditions, initially targeting 1 USD per YAM”, and additionally buying yCRV tokens with the supply expansion and placing these in the Yam treasury.

YAM was a monetary experiment, composed of several other monetary experiments wrapped together in a package that didn’t quite work.

But the YAMs were just an appetiser for a more substantial meal with several courses, featuring food tokens from up and down the pyramid and most notably SUSHI. I have written an overview of Sushiswap and Uniswap, focusing on their governance and recounting a version of the story so far. Some highlights for this post are:

- Automated Market Makers (AMMs) are a novel way of creating markets that don’t rely on the conventional order books but instead have participants add and withdraw tokens from pools to make trades, with smart contract logic determining prices.

- Bancor pioneered AMM pools, but Uniswap popularised the idea with a method that didn’t involve buying special tokens to participate.

- SushiSwap copied Uniswap’s smart contracts, dropped the idea that a fee would be added to compensate VC investors and added in a SUSHI token instead, which would be distributed to all of the liquidity providers (effectively the people who run the AMM service). This also incorporated a “vampire attack”, where SUSHI tokens were being offered specifically to Uniswap liquidity providers at an attractive rate, so as to lure them and their liquidity into the competing SushiSwap pools.

- The story had drama, when Chef Nomi made an abrupt transition from being the hero who founded SushiSwap to liquidating the entire SushiSwap dev fund and pocketing the ETH. The Chef would later return the ETH, and it would be converted back to SUSHI, but his reputation in the community had been irreparably damaged.

- Uniswap subsequently added a UNI governance token which works in a very similar way to SUSHI, and made a retroactive initial distribution of these tokens to people who had used the Uniswap decentralized exchange. The UNI token started trading at around $2-4, and 150 million tokens were distributed initially, so this amounted to an almost instantaneous creation of about ~$500 million in value. In UNI’s case the token was capturing value that had been developed in the protocol with a claim on its future governance and some fee revenue - but SUSHI performed similar alchemy with largely borrowed tools.

- Uniswap won most of its liquidity providers back from SushiSwap when UNI launched, but as initial bonus incentives expired and SushiSwap responded with more of its own bonus schemes the liquidity has started to tilt back in SushiSwap’s direction. In either case it seems there will be ongoing competition between these protocols, and one of the only differentiators will be their governance.

- The overview covers the governance of the respective projects in some depth. While similar in outline the use of the proposal systems is very different in the production environment, due largely to the different thresholds for creating and approving proposals. Just before the end of 2020, Uniswap had its first governance proposal approved, to fund a grants program with up to $750K quarterly. The program will be administered by a committee of 6 members with 1 lead (all named in the proposal).

Yearning for Decentralized Finance

Yearn Finance, with governance token YFI, is a set of smart contracts created by Andre Cronje which aims to provide access to yield-farming and other profitable opportunities to people who put their assets in vaults that manage allocated funds according to a specified strategy. Brady Dale of Coindesk has written extensively about what Yearn is about 26 and the manner in which it has expanded through a series of mergers to position itself as the “Amazon of DeFi”. 27

Yearn, and a similarly purposed Harvest finance, serve as an easy on-ramp to engaging in DeFi yield maximizing, their aim is to do this for the user within defined parameters. This allows more capital to be engaged in these markets and pools than would otherwise be the case.

In terms of Yearn’s governance, it is worth noting that it had a “fair launch”, with no premine of the YFI token. Early in the project’s history it was decided to issue 30K YFI tokens to people who were providing liquidity over a one week period. This is how all of the YFI tokens were issued, and the YFI holders have subsequently voted to reject proposals to issue more YFI.

The path taken by Yearn and Uniswap is in line with the playbook28 Jesse Walden published at the start of 2020, that seems to have been quite an influential document.

Governance takes place primarily in the forum and snapshot is used for voting. Snapshot signal voting is popular among Ethereum projects which use voting in their governance, as it allows for votes to be cast without incurring gas costs. Snapshot was developed by Balancer labs, another DeFi project.

Control of the YFI minting contract was put in the hands of a 6 of 9 multi-sig Gnosis Safe, and Andre Cronje removed himself as one of the controllers. This was seemingly done because Andre had the exclusive rights to mint YFI before and this became a bigger key man risk with the rise in value of YFI. The forum post refers to another forum post with details of the on chain voting system for approving changes to smart contracts, but at the time this appeared to be largely aspirational and still at the “Andre does it manually” stage.

As Yearn has embraced a strategy of partnership and mergers in recent months, the prize vegetables from the year’s bumper food token crop which didn’t rot in the heat of DeFi summer are now being combined, and the table is set for a soup-er 2021 (puns intended, sorry).27

It’s on fire!

When it comes to the DeFi space as a whole, hacks and failures (sometimes spectacular) have been a regular occurrence in 2020.

There have been a great variety of these, including some novel types previously unseen, such as the flash-loan attack pioneered 29 on the bZx Ethereum dapp. A flash loan is a novel type of credit offering where large sums can be borrowed with no collateral but must be paid back within the same block. In other words, a flash loan only works as part of a chain of transactions, all executed within the same block, starting with the loan being taken out and ending with its repayment in full. If anything goes wrong with the series of transactions and the amount is not repaid, the flash loan simply fails to make it into the blockchain, and leaves no trace.

The atomic resolution virtually eliminates risk to the lender’s capital, and this means they can lend to anyone with good assurance of being repaid, plus one assumes a fee to make it worth the lender’s trouble. This has a levelling effect, because previously the amount of money one could make from exploiting bugs in DeFi smart contracts was limited by the amount of capital one could deploy.

This paper by Qin, Zhou, Livshits & Gervais 30 dissects the first two flash loan attacks in detail, and offers notes on how to increase the profitability of the technique. The technique for these hacks involved using some of the loan to manipulate a price oracle while using the rest to make transactions which would profit from the manipulation. The first two flash loan attacks netted less than $1 million, whereas as the year went by the sums being gained by people using flash loans to exploit smart contracts increased considerably. Someone flash harvested31 $24M from Harvest Finance in October, flash spoils of $7M, $6M, $2M in November - and those are just the recent examples.

The fault here lies primarily with the DeFi protocols which have such weaknesses, the flash loans just open up the possibility of making money from these exploits to people who don’t have their own capital to deploy. This seems to be the emerging consensus.32

According to ciphertrace’s blog post 33 DeFi accounts for around 48% of the number of crypto hacks/thefts, and around 30% of the volume of lost funds - up from virtually negligible last year.

As an outside observer, the impression that the more vocal “DeFi degens” make on twitter is that they’re in solid profit and can take these losses on the chin.

Seeing the Ethereum community pile hundreds of millions of USD worth of crypto assets into novel smart contracts is an interesting spectacle. The speed of development and deployment, and the gusto with which pools are filled with assets, echo the “move fast and break things” style of development - for the community it could be extended as “move fast and tolerate risk”. This feels to me like one of the characteristics of blockchains which align with personality traits, such that people will be drawn to different projects based on how comfortable they are with risk and complexity. If we consider the range of “potentially hazardous unknown events” that could befall users of Bitcoin as compared to dForce, for example, it’s a totally different ball game.

Dark Forests in Ethereum Land

Flash loan attacks are an example of a profitable transaction which could be executed by anyone, and so they are in theory susceptible to poaching or front-running by miners and other nodes which will relay the transaction to miners. This kind of front-running has been observed previously by Daian et al. (2019)34 and given the label “miner extractable value” (MEV).

I enjoyed two articles about dealing with this “dark forest” (referencing the “Three Body Problem” science fiction series) from the perspective of developers who were aiming to “rescue” some vulnerable funds. In the first one 35, by Dan Robinson and Georgios Konstantopoulos, the protagonists try to sneak a burn transaction past the mempool bots which they suspect are lurking, but it gets picked off in a few seconds and the miner pocketed $12,000. The second36 story on this subject, from samczsun, had higher stakes, benefitted from lessons learned in the earlier attempt, called in expert help, and was ultimately successful in the rescue of $9.6 million which had been sitting in a vulnerable smart contract by enlisting the help of a miner who could mine the transaction directly. I thought both of these were well written and interesting accounts of the true nature of the Ethereum mempool and one of the ways in which miners exert control over the network.

Doxxed hackers and donations

There have been a few DeFi-related incidents in 2020 that ended with the attackers giving some or all of the ill-gotten tokens back. Perhaps most notably, whoever hacked the dForce smart contracts for $25 million of deposited crypto went on to return almost all of it, $23.8 million (they lost money on some trades before returning everything). In this case it seems clear that the hacker’s identity was exposed and they opted to return funds to avoid possible repercussions.

Doxxing, or having one’s identity exposed, is also a possible explanation for Chef Nomi’s return of the Sushi development funds.

One of the larger hacks of the year had a more conventional and centralised target, the Kucoin exchange, which was hit for $275 million. A report 37 by Chainalysis gives details of how the hacked funds were processed and make a point about the growing use of DeFi decentralized exchanges to swap the tokens into something less obviously stolen, making it more difficult for exchanges to block transactions which use these stolen funds. The trace is easy for an outfit like Chainalysis to follow however, and they seem to have been involved in providing information which led to the freezing or burning 38 of a significant proportion (~65%) of the stolen tokens.

This relates back to the point above about the foundations of DeFi (and dapp tokens generally). The following projects were able to move swiftly to censor the hacker’s funds: Orion Protocol, Covesting, Kardiachain, Velo, VIDT, SilentNotary, Ocean Protocol and Tether.

I have been spending some time analysing the Decred blockchain in 2020, and I have seen for myself the unreasonable effectiveness of address clustering.39 UTXO chains like Bitcoin and Decred afford more options for tactical use of addresses, as a wallet can generate many addresses and these are not linked unless used at the same time (as common inputs to a transaction). Without careful UTXO selection, addresses are likely to be combined in such ways as to allow someone who knows about one of a user’s transactions to know about many more of their transactions and balances.

Ethereum is account-based, and this presents further challenges, it is perhaps a more difficult environment to protect one’s privacy in. It is noteworthy however when even people with presumably a high degree of proficiency with this technology (enough to exploit a bug in a smart contract) have to give their loot back because they revealed their identity by mistake.

Cryptocurrency is a double-edged sword when it comes to illicit uses. Censorship resistance (where this is actually provided by the cryptocurrency) means nobody can stop its use for a criminal purpose, but the price is sharing details of one’s transactions with thousands of nodes around the world to be included in a permanent public record.

This is not just a problem for criminals, but anyone who could become a target if details of their cryptocurrency transactions or holdings became known to nefarious actors. In my view this is a significant obstacle to a future where self-custodied cryptocurrency is common among the general population. Privacy is a major component of practical security when it comes to cryptocurrency.

There have also been some crypto donations by hackers who weren’t necessarily exposed but maybe just felt like indulging in some Robin Hood type behaviour.

One such instance concerned DeFi legend Andre Cronje, who was testing a new protocol/token (EMN) in prod and tweeting about it when overnight people deposited $15 million worth of assets into the new unaudited contracts and it all got taken by someone who spotted a flaw in the contracts. Half of the funds were returned to the contract which Cronje controls, and he tweeted that they would be distributed to EMN holders based on a snapshot of addresses.

Maybe this is catching on as part of a broader trend, because it seems like now a group of ransomware hackers have started making charitable donations.40

Decentralized Governance

It has been an exciting year for blockchain governance with many projects launching formal voting-based governance systems, increasing both the level of this kind of activity and its visibility within the cryptosphere. While it is good to see more people taking blockchain governance seriously and even getting excited about it, I feel like some of them are in for a disappointment when they see how the governance of their particular project(s) of interest develops.

There’s a pattern here of teams deciding they need a token to monetize their project, at which point governance is an obvious thing that a token could do which might make it desirable, so an obvious choice. In many cases the token is the answer to questions about how to monetize, not the natural answer to any questions about governance.

Would you like governance with your food tokens?

This recent article from Hasu 41 makes a strong case for avoiding token-based governance where it is not needed, in particular where it puts people in control of something that shouldn’t be changed. This is particularly relevant where authority to edit smart contracts can expose deposits to confiscation. Hasu finds that his position on tokens has changed such that he is now in favor of tokens for liquidity mining and bootstrapping, but sees value in the promise of fee revenue or some other form of equity as the driving force, with governance an often unnecessary afterthought. Hasu makes a distinction between areas where human input is required and worth paying for and aspects where it is not necessary - with the independent liquidity pools of Uniswap and Sushiswap being examples where individual pools could be allowed to fail without damaging each other.

It feels to me like a lot of projects embraced token-based governance this year without having much experience with it, and they’re going to be experiencing some friction around ill-fitting voting systems. Whether they make it work or not probably depends as much on what’s happening off chain in their communities, whether people are engaged and motivated to route around problems - or waiting with their bag by the door (or on the exchange) for a good exit opportunity.

DAOs

After reviewing the state of the DAOs in 2020 I’m frankly a bit disappointed, my impression from following it casually over the year was that things were really moving forward for some DAO platforms. Closer inspection revealed a less optimistic picture, with more DAOs seeming to fizzle out than roar into sustained activity. There are a few brighter exceptions, but if you’re thinking you might want to skip the DAOs <- that link has you covered, I won’t judge.

The excellent deepdao.io dashboard now offers a way to easily find DAOs built on the most popular platforms, along with a selection of high level metrics about them. I’m using it extensively to find DAOs and download data-sets representing aspects of their activity, and it’s making my life a lot easier than when I had to navigate these DAOs on their own platforms, which tend to be laggy and omit critical information like dates.

Let’s check in on the DAO platforms covered by cryptocommons.cc to see what’s new.

Aragon

Aragon had a big year in terms of major features that attracted significant attention in the ecosystem. The ANJ token was launched, used, and by the end of the year is set to be retired. Aragon also benefitted from adoption by some DeFi communities in need of a drop in governance solution.

ANJ comes (and goes)

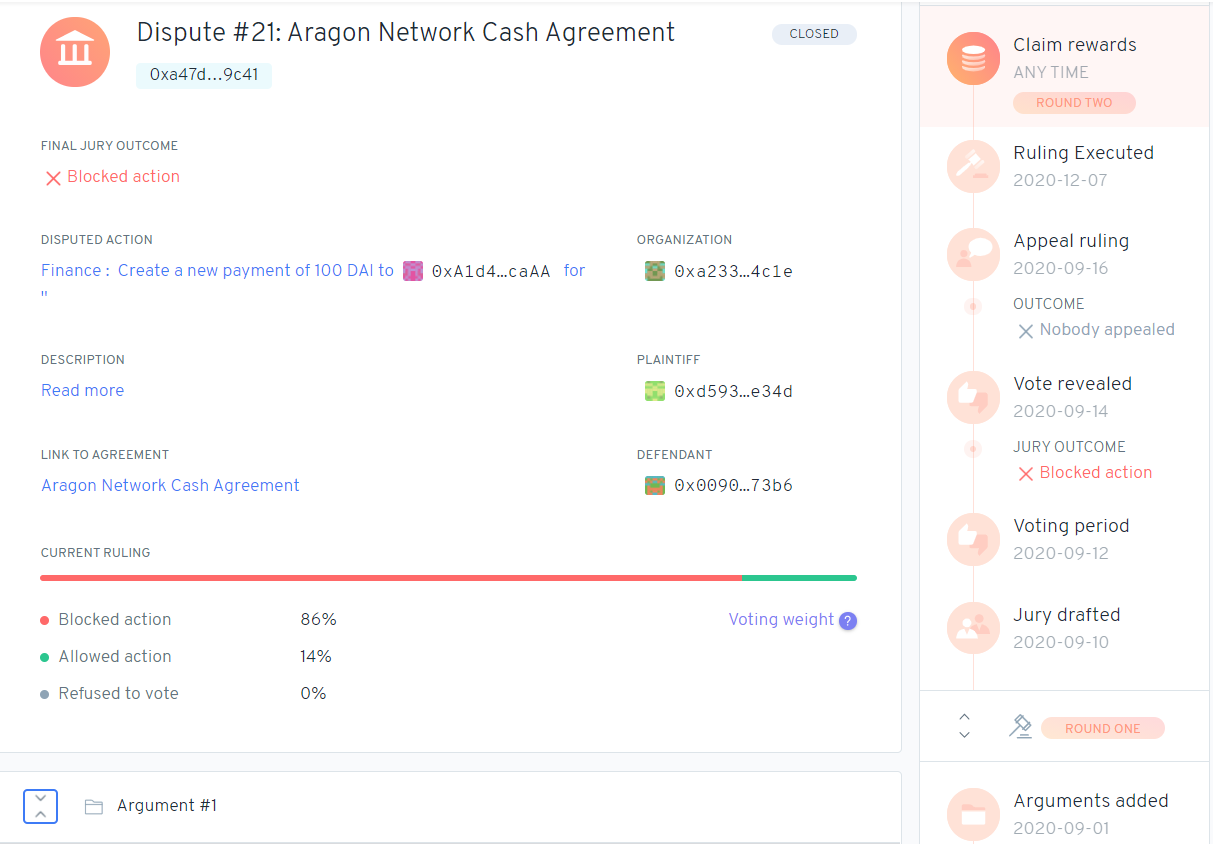

Aragon Court is a dispute resolution service for DAOs, it is intended to allow for “Aragon Agreements“42, which allow for agreements specified in human language as opposed to code, to be arbitrated. The idea is that Aragon jurors will adjudicate disputes by playing a Schelling game where they profit by choosing the same answer as other judges. People who wanted to participate as jurors could buy ANJ tokens or stake some ANT (Aragon’s existing governance token) to get these, and their chance of being called on to act as judge in a particular dispute was proportional to their ANJ at stake.

Aragon Court opened with a “precedence setting” campaign43 of mock disputes, where scenarios would be deliberated and worked through the system as if they were real, to test the system and establish basic norms for how jurors should vote. In what was a fairly major faux pas, the first dispute was based on a real case that had recently received attention in the crypto sphere, the actors involved were not consulted and felt uncomfortable having their case worked through the Aragon Court system. Aragon had to apologise44 and void the mock dispute.

One of the example disputes, involving a payment for Google Analytics

So far all 22 disputes to go through Agaon Court have been of the mock variety. In the example above someone wanted a payment to integrate Google Analytics, but the (only) argument in the case, brought to block the payment, was that this contravened an Aragon Manifesto principle of using technology as a liberating tool. The Aragon Court jurors chose to block the payment to integrate Google Analytics in this case, with an 86% majority.

It looks like the point here is to demonstrate that Aragon isn’t into tracking people, but it also paints a picture of Aragon Court as a service whereby outsiders (Aragon Jurors) will look at vague documents like a manifesto and translate them into executive decisions about the operation of your organisation or protocol.

After an aborted attempt to quickly merge ANJ into ANT, the Aragon One leadership set out a more community-led process where holders of both ANJ and ANT would get some say. The outcome of this process was fairly close to the original proposal, ANJ holders would be offered ANT at a rate of 0.015 ANT per ANJ, or a higher rate of 0.044 ANT/ANJ if they lock the ANT for a year. This will result in ~1.5-4% new issuance of ANT tokens, so in effect the ANT holders are buying out the people who participated in the ANJ experiment.

All change at Aragon

It’s all change at Aragon in 2020, in addition to the creation and disbandment of ANJ there was:

- Sunsetting of Aragon Chain development in favour of supporting deployment on token-agnostic Ethermint chains.

- The end of the AGP process which has allowed ANT holders to signal on proposals to spend development funds, this is being replaced with a 5 person council in phase 2 of the “Aragon Network” launch. ANT holders will be given more control of the “Aragon Network DAO” in phase 3.

- The Aragon Flock grants program was dissolved, and later the Nest grants program too, a final report on Nest gave spending figures of $1.5 Million and 271K ANT (~$888K at December 2020 price of $3.28/ANT).

- The ANT token was upgraded to ANT v2, which will be cheaper to transfer and support gasless transfers and adoption of off chain voting in Aragon v2.

- Announcement of “Aragon Govern”, which is a streamlined developer-focused DAO framework.

From the DeFi space, Bancor, Aave and mstable have adopted Aragon DAOs and put significant assets under their management, although their DAOs are so far not particularly active.

I also noticed an interesting proposal under discussion in the yEarn community, where Jorge Izquierdo (Aragon founder) was pitching Aragon Agreements as something that YFI should use in Sep 2020, before 2 months later the thread closes with him explaining that the plan changed and he will return with a new plan at some point.

How about those Aragon DAOs

Now for a look at what the 50 Aragon DAOs tracked by DeepDAO have been doing. When I looked at Aragon DAOs in 2019 it was hard to find the interesting ones, even after asking around - this year DeepDAO has me covered with a nice list that I can export to csv!

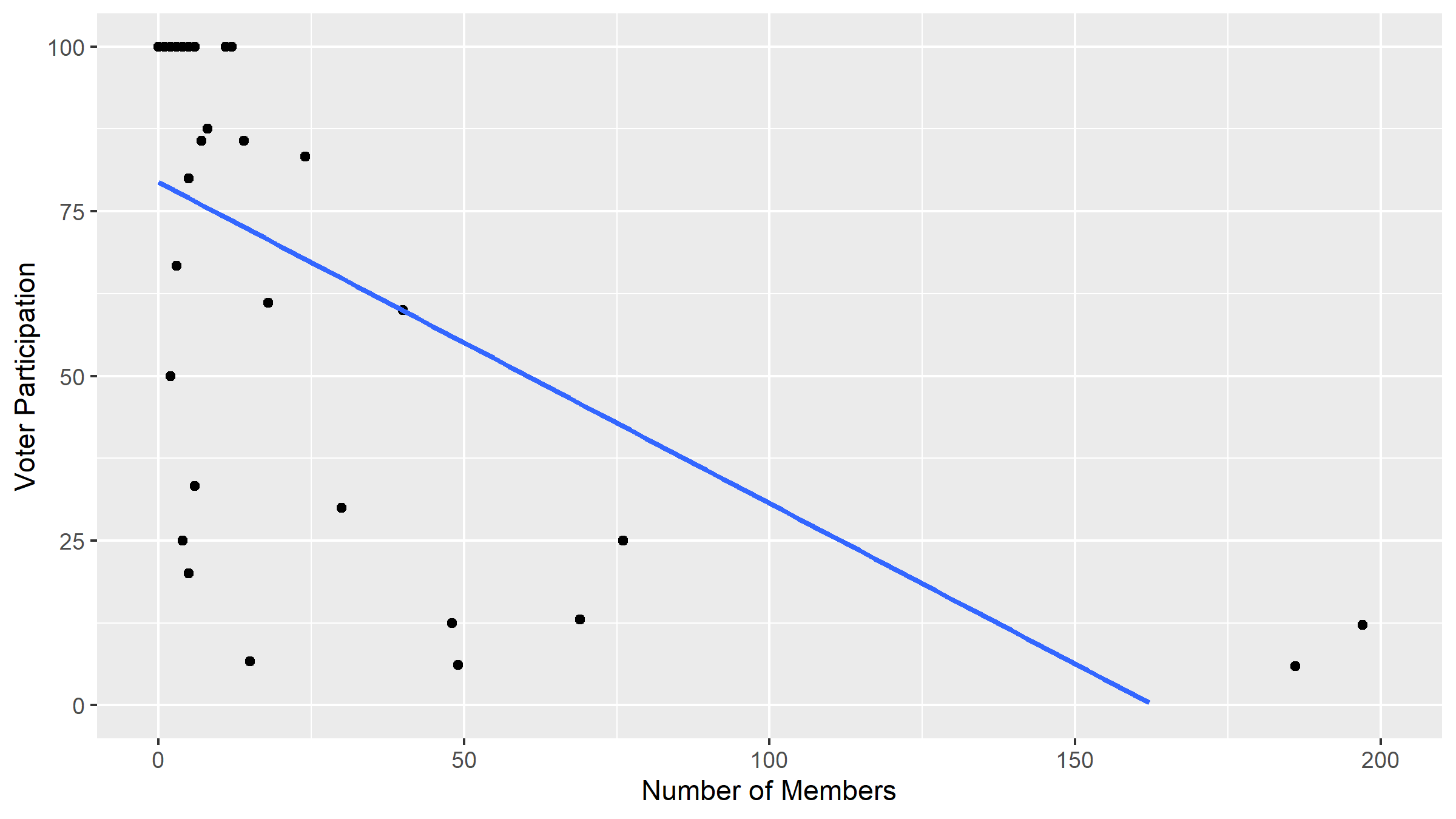

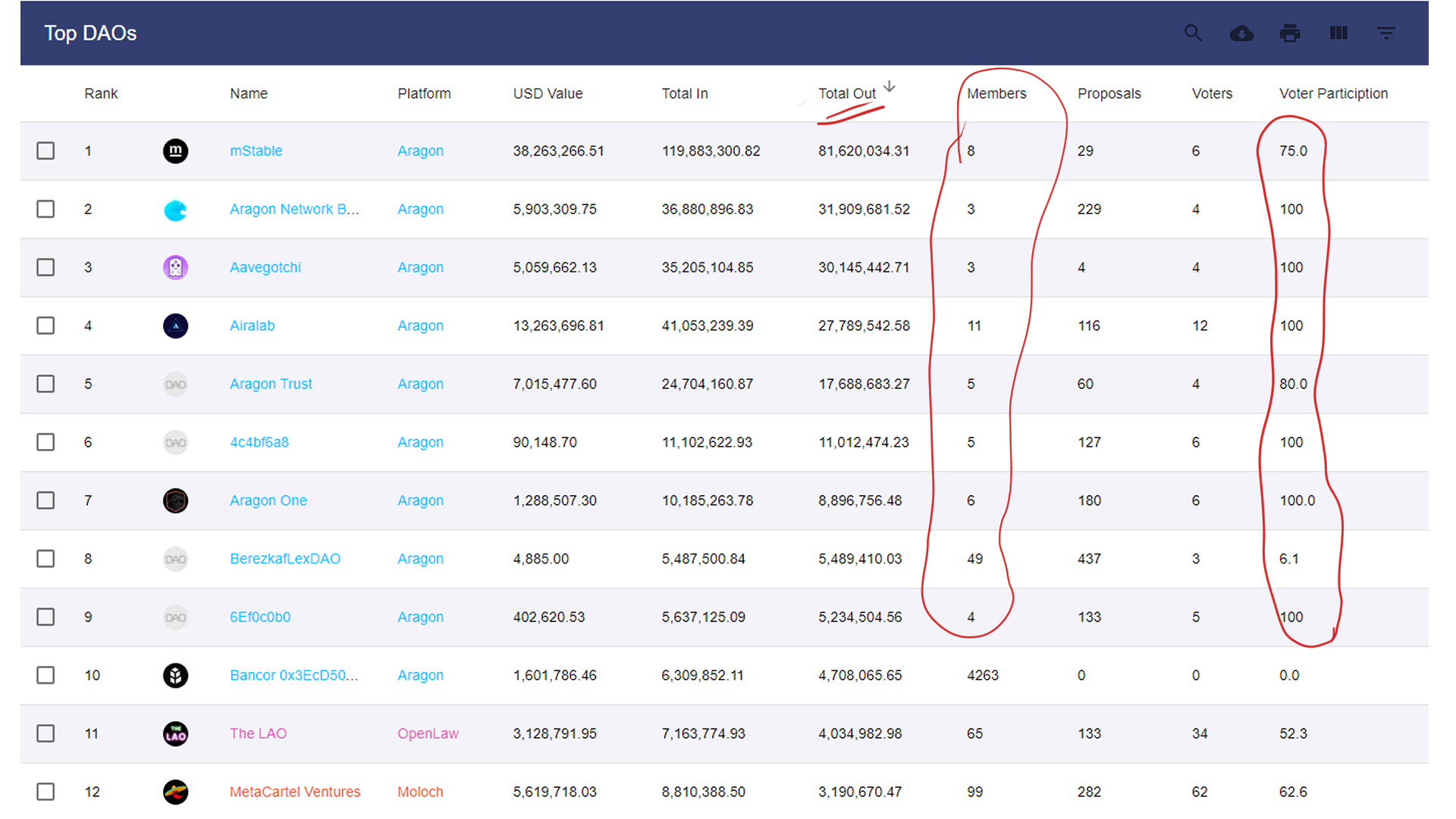

Some of the metrics for these DAOs are highly skewed, to the point where there’s little point graphing them. The 3 largest DAOs have membership in the 1,000-5,000 range, but two of these have no proposals, and the other (PieDAO) has a single proposal which was voted on by just 6 members out of 3,128 total members. The two active DAOs with the most members have membership in the 100-200 range, but 38 out of 50 DAOs (76%) have 20 or fewer members. The maximum number of voters in any Aragon DAO is 24.

Scatterplot showing number of members per Aragon DAO and the voter participation (in terms of members) of that DAO - excludes 3 DAOs with >200 members. Data sourced from DeepDAO.

There is a clear relationship between the number of members of each DAO and its voter participation rate, as shown in the figure above. More members in a DAO means a smaller proportion turning out to vote. This is something you would expect to see in many systems, as the smaller the relative influence of a single voter the less it makes sense for them to spend time in exercising that influence (reading about proposals and voting).

It should be noted that the source data for above figure has values of over 100, I set these to 100 but they may indicate some underlying issue with the reliability of the measure.

Big-spending multi-sig DAOs

The DAOs that have spent the most are operated by a few individuals each, with typically high participation in proposals. These DAOs are performing functions similar to multi-sig wallets, albeit according to some breakdown of tokens as opposed to each participant having a part of the signature. Some of these DAOs are operated by the same people who are building the Aragon platform, so it is for them a case of eating their own dog-food. All of the DAO platforms engage in this kind of dog-fooding to some degree.

The DAOs that have spent the most, have low number of members and high vote participation. Data sourced from DeepDAO.

Put your best DAO forward

On the Aragon platform 6 DAOs are highlighted, so I have also looked at those specifically.

- Lightwave has 3 token holders with an even split of tokens, it went from a max budget of 1.5 ETH to 0.2 in March 2020 and hasn’t seen a proposal since.

- BrightID is a “social identity network” which aims to allow users to prove that they are unique human, its DAO has seen 101 proposals through which $780K has been spent (of $924K in). There are 11 members with an equal share (~9.1% tokens each), and they were a very agreeable bunch, with 98 or 101 proposals decided unanimously with no dissenting votes. This one operates on a minimum approval threshold where a proposal must get yes votes from >50% of tokens to be approved, and most of the proposals to fail did so without meeting this threshold, there have been 16 rejected proposals and only 1 of these had more no votes than yes. Some of these rejected proposals were simply supplanted by a subsequent proposal, this is common to many DAO communities where flawed proposals cannot be retracted and must be rejected. Most of the proposals concern payments to workers and for organisational expenses, but there are some other types also, such as a proposal to stake tokens for the Commons Stack community.

- Livepeer is a decentralized video transcoding network and its DAO seems to have been operating from April - December 2019, it saw 30 proposals to spend LPT tokens and then all its LPT was spent and people stopped voting on proposals.

- Similar timeframe for the MyBit DAO, and the project lead leaves no room for doubt with a reddit post that opens with “Hey everyone, so as I am sure most (or all) of you agree is that the project is kind of a total mess in its current stage.” and explains how the remaining funds will be liquidated to held by their company.

It is clear that the rise in the cost of Ethereum transaction fees in 2020 has been hard on Aragon’s DAOs, which are quite heavily “on chain” entities, and so have limited room to manoeuvre without incurring costly fees. The move to embrace a new protocol that can do more off chain, and to proffer Aragon Court as an accompaniment to something like Snapshot, are in a way pivots around the bad user experience of on chain interactions.

Moloch

Moloch is a set of Ethereum smart contracts which form a DAO, people submit tribute with their requests to join and the tribute of members forms the DAO’s treasury. Members vote with their shares on whether to spend some tribute to fund proposals. The smart contracts for Moloch have been cloned many times by different groups to create their own Moloch style DAOs, one of these is considered in the following section.

The original Moloch DAO launched in February 201945 for funding development of the Ethereum ecosystem. Members of the DAO have non-transferable shares which they can use to vote on proposals. The DAO is funded by “tribute”, when new members join they add resources to the fund. It is in a sense a DAO for collectively administering donations. Moloch v2 smart contracts launched on Jan 1 2020, they simplify using the DAOs by creating easier ways to claim funds than ragequitting and are specifically adapted to work with legally compliant DAOs (see below).

The DAOHAUS site serves as a portal listing DAOs in the Moloch mould, along with instructions for “summoning” one of these.

Moloch DAO

The original Moloch DAO is proceeding as planned, dispensing funding for Ethereum ecosystem projects. It is up to 76 members, 130 proposals have been voted on (includes 66 proposals to add new members), and it has a remaining balance of 3,000 WETH.

It’s not straightforward to measure share participation in Moloch proposal voting because the total number of shares changes regularly are these are issued and redeemed - I would note however that the voter participation rate currently listed for Moloch on DeepDAO (57%) is heavily influenced by early proposals. When a new Moloch DAO is summoned there is typically one proposal each for every member who joins, and this may be facilitated by whoever summoned the DAO and became its first member.

It is much easier to look at Moloch participation in terms of number of users, because every address represents an individual member which went through its own application process (although Ethereum Foundation has 10 numbered “seats”).

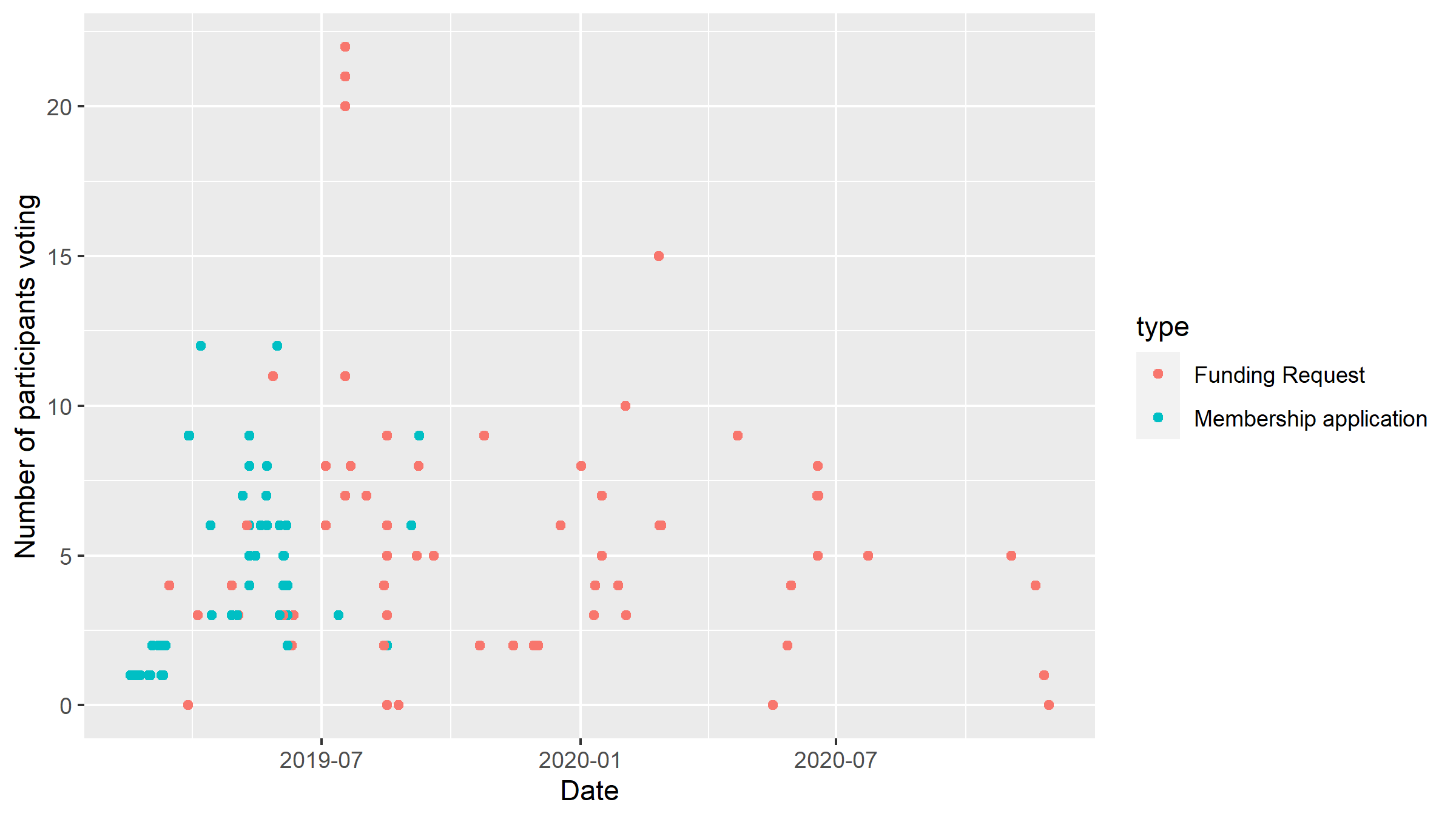

Moloch proposals and the number of members who voted on each

The mean number of members who vote on a proposal is 5, in 2019 this covers a period where there were many proposals to onboard new members which had just 1 vote each, and also a period of greater voting activity. In 2020 the mean for the year is 5.4. This is not very high turnout, a few members are making decisions on behalf of the DAO. Moloch is however designed to accommodate this, with the option for members to ragequit and reclaim their share of the pot if they don’t like a proposal.

The graph indicates a slowdown of proposal activity over the course of 2020 thus far.

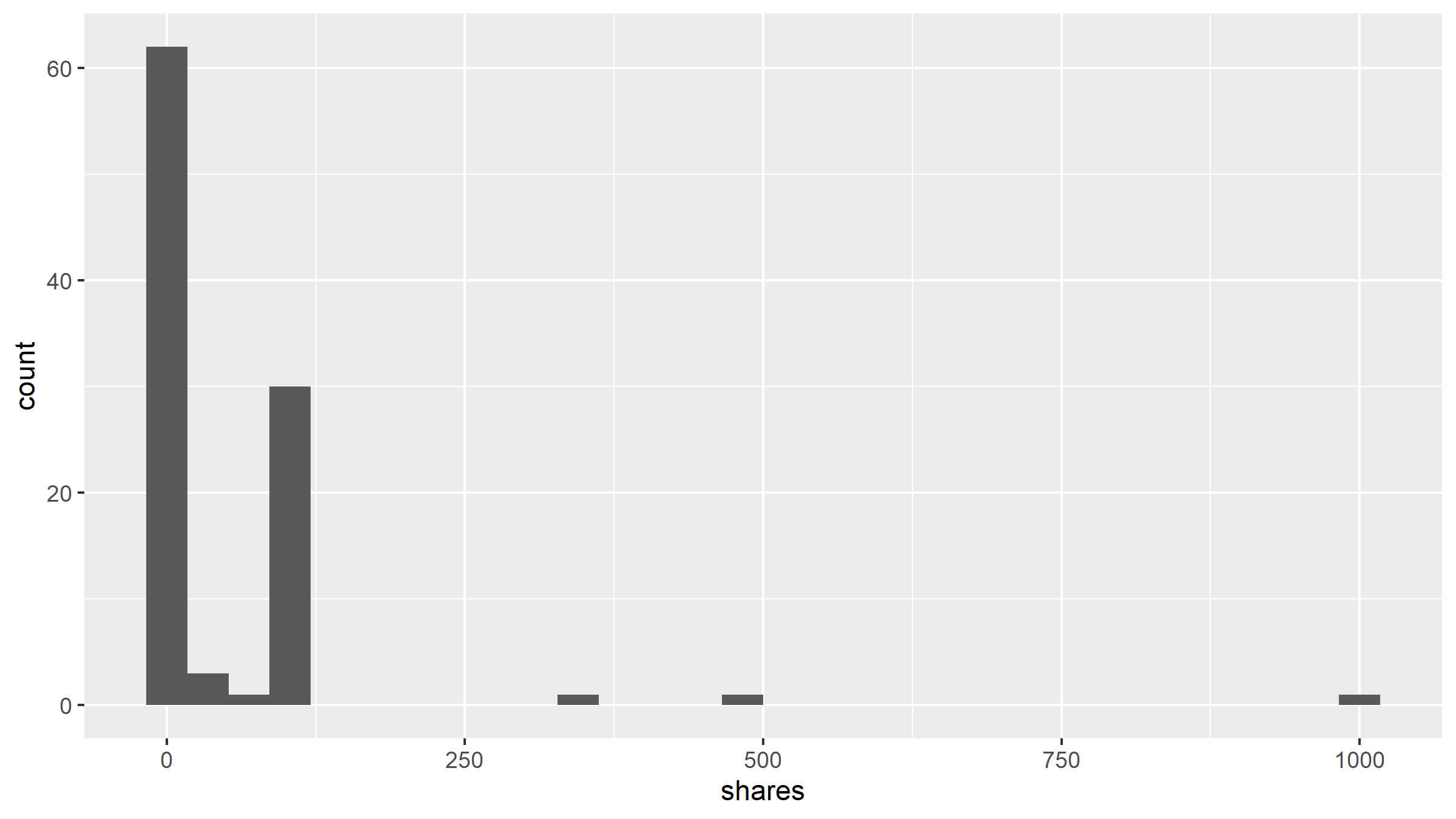

Moloch members histogram

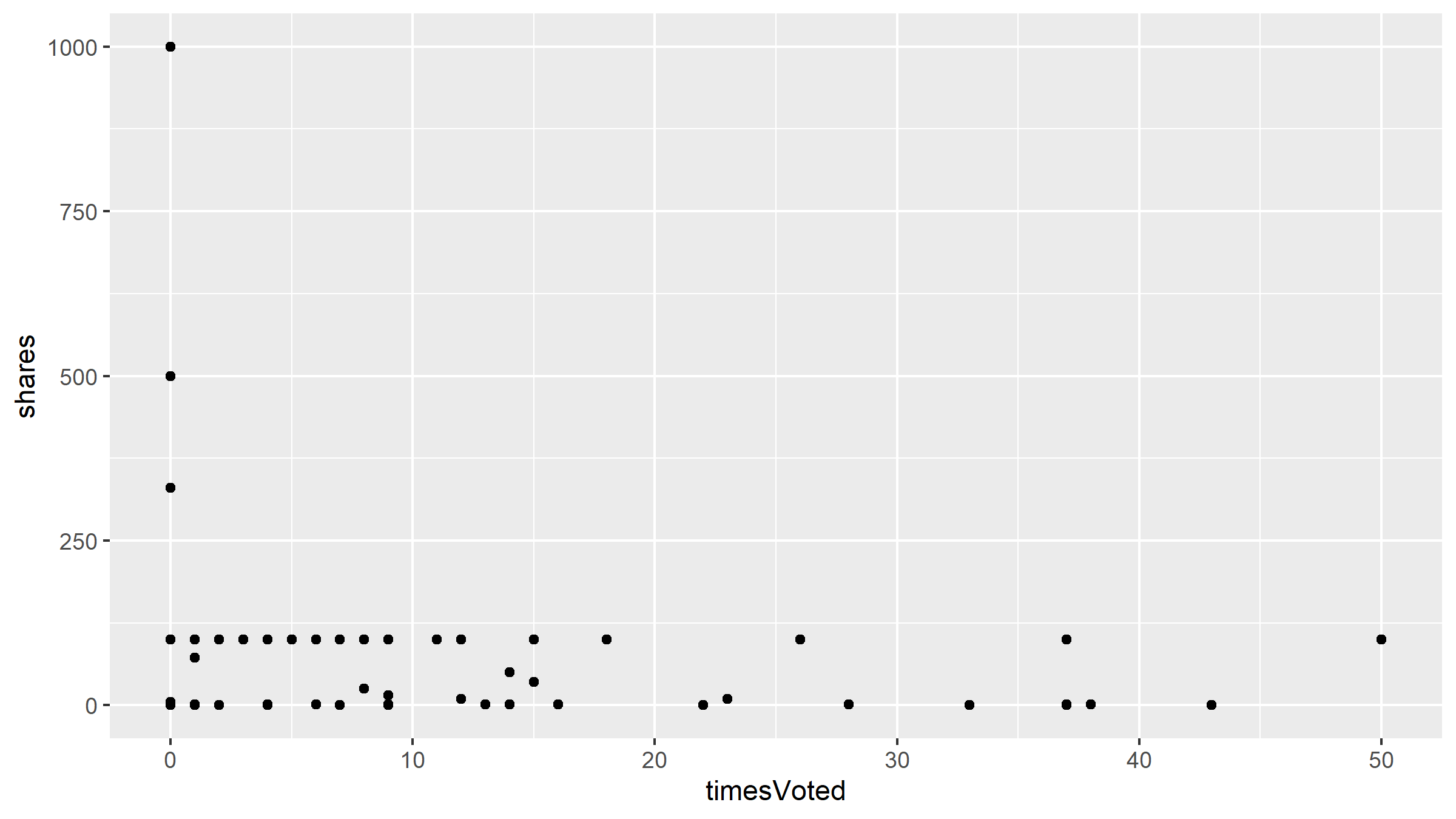

Moloch members shares and number of votes

The way it is being run, it seems to be used as a vehicle for the large members (who provided the most tribute but don’t vote) to soft delegate spending decisions to members with lesser stake but who are (presumably) putting in the time to consider funding request proposals in detail before voting on them. Notably the 3 largest shareholders have never voted.

Among the voting members however there is a divide (according to DeepDAO data) between those with ~100 shares and those with ~1 share, the latter group having little effective say.

MetaCartel (Ventures)

MetaCartel was one of the largest Moloch clone DAOs and it served to distribute funding to an “ecosystem of DAPP builders” in the form of grants. According to DeepDAO, MetaCartel dispensed $620K in funding (not counting $355K which was migrated to v2), seeing a total of 137 proposals approved of the 146 submitted.

MetaCartel migrated to a Moloch v2 DAO, these upgraded contracts allow funds to be issued in a less convoluted way that does not require the recipient tom ragequit shares to receive spendable funds. The v2 DAO is still going, it has $60K left from the $443K it has received to date.

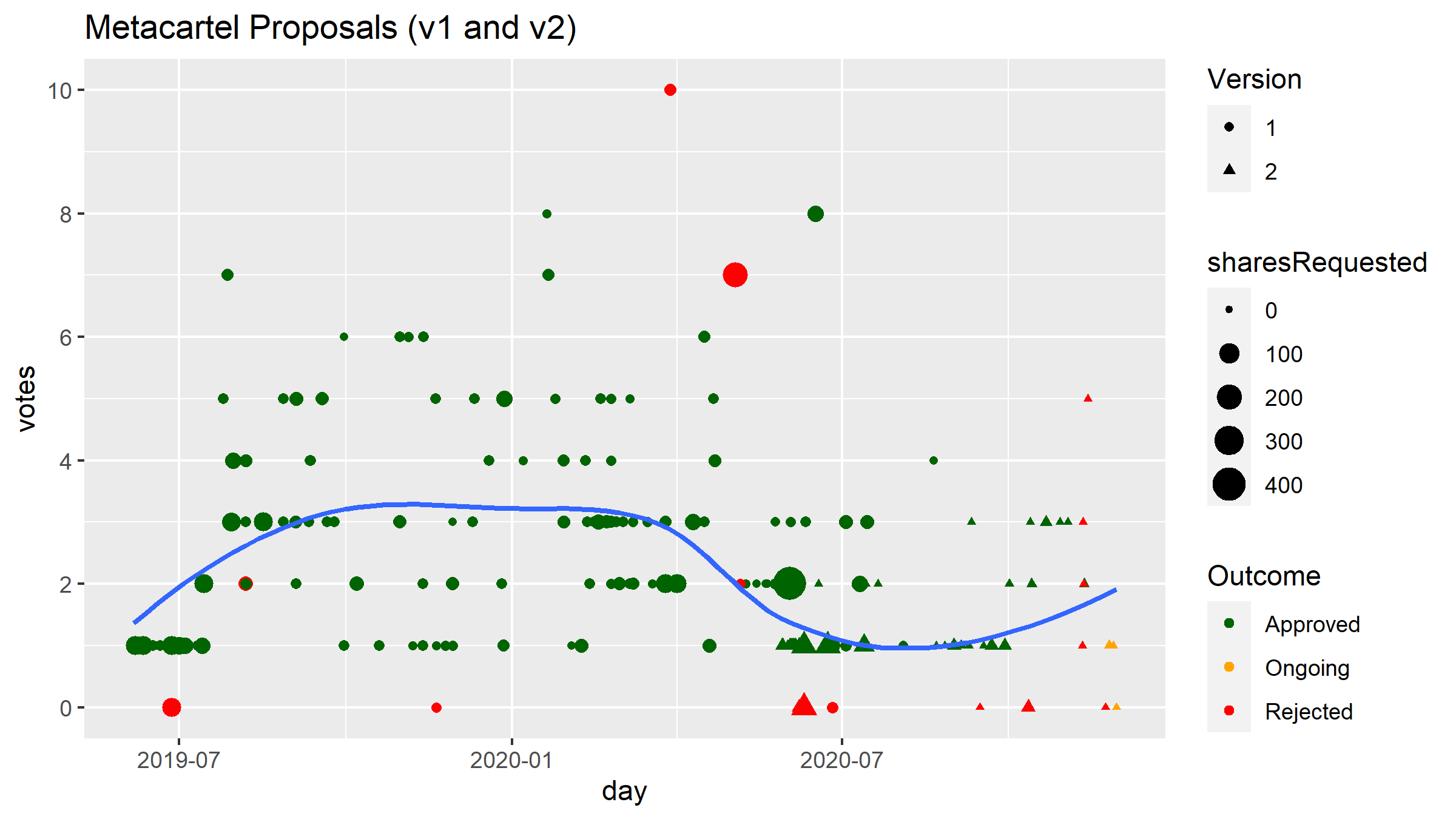

MetaCartel DAO Proposals: Number of voters (Y axis), version (1 or 2) and shares requested (size)

From the graph you can see that the number of accounts voting on each proposal is fairly small, for v2 this has dropped down to 0-3 voters per proposal. Most of the proposals that are voted on pass, with many rejections happening without anyone voting on the proposal.

MetaCartel also has a bigger sister DAO now, MetaCartel Ventures, which is a pivot to DAO as instrument of a conventional for-profit enterprise 46 - or in other words, the DAO funders are now able to take equity positions and other considerations in exchange for funding. This DAO has a much larger balance, with $6.1M AUM (Dec 12 2020), and having already spent $3.8M. There is a private forum where details of deals are shared with DAO members, but the votes are publicly visible, and one can see that recently approved investments include Rarible and BrightID.

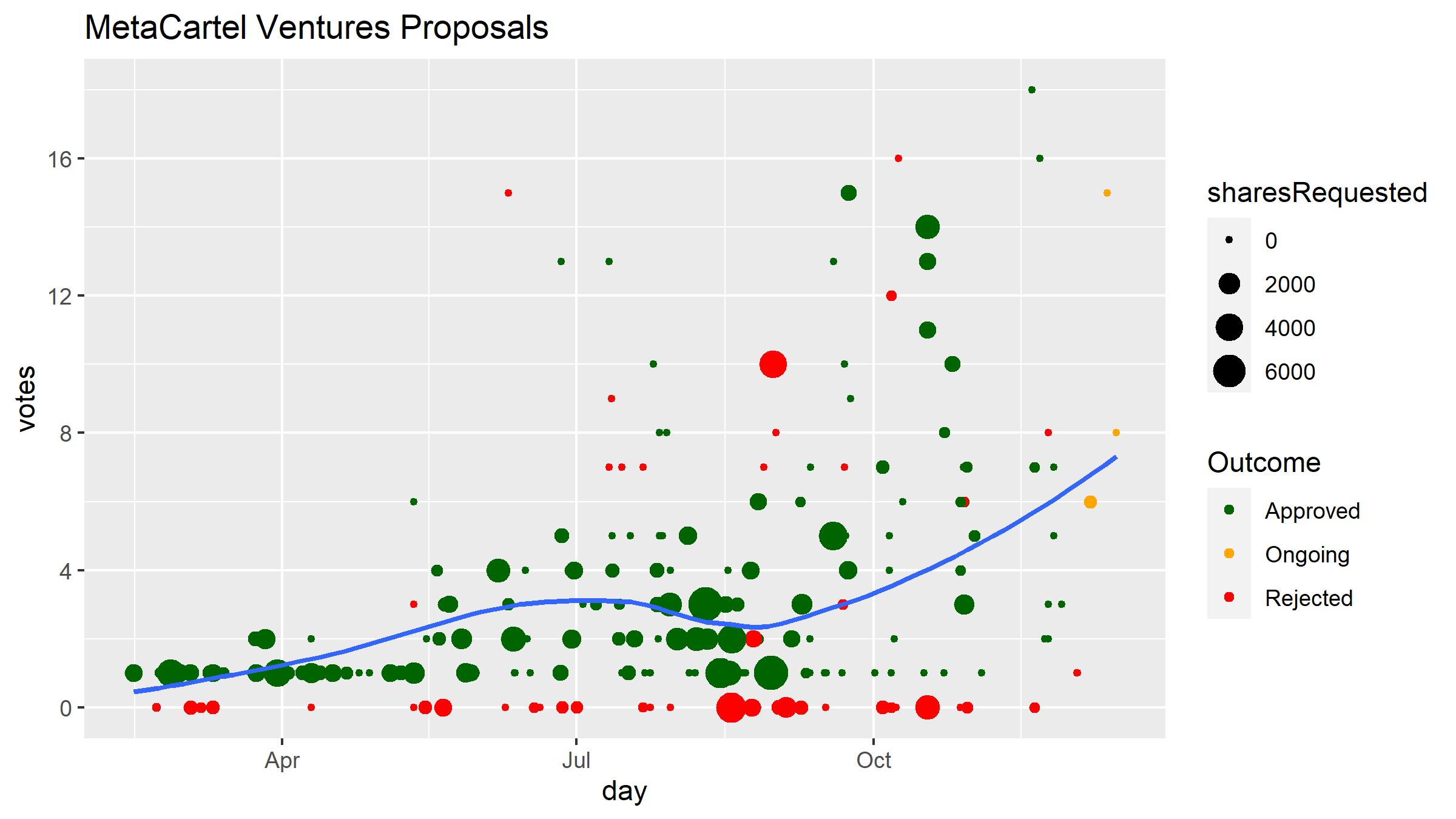

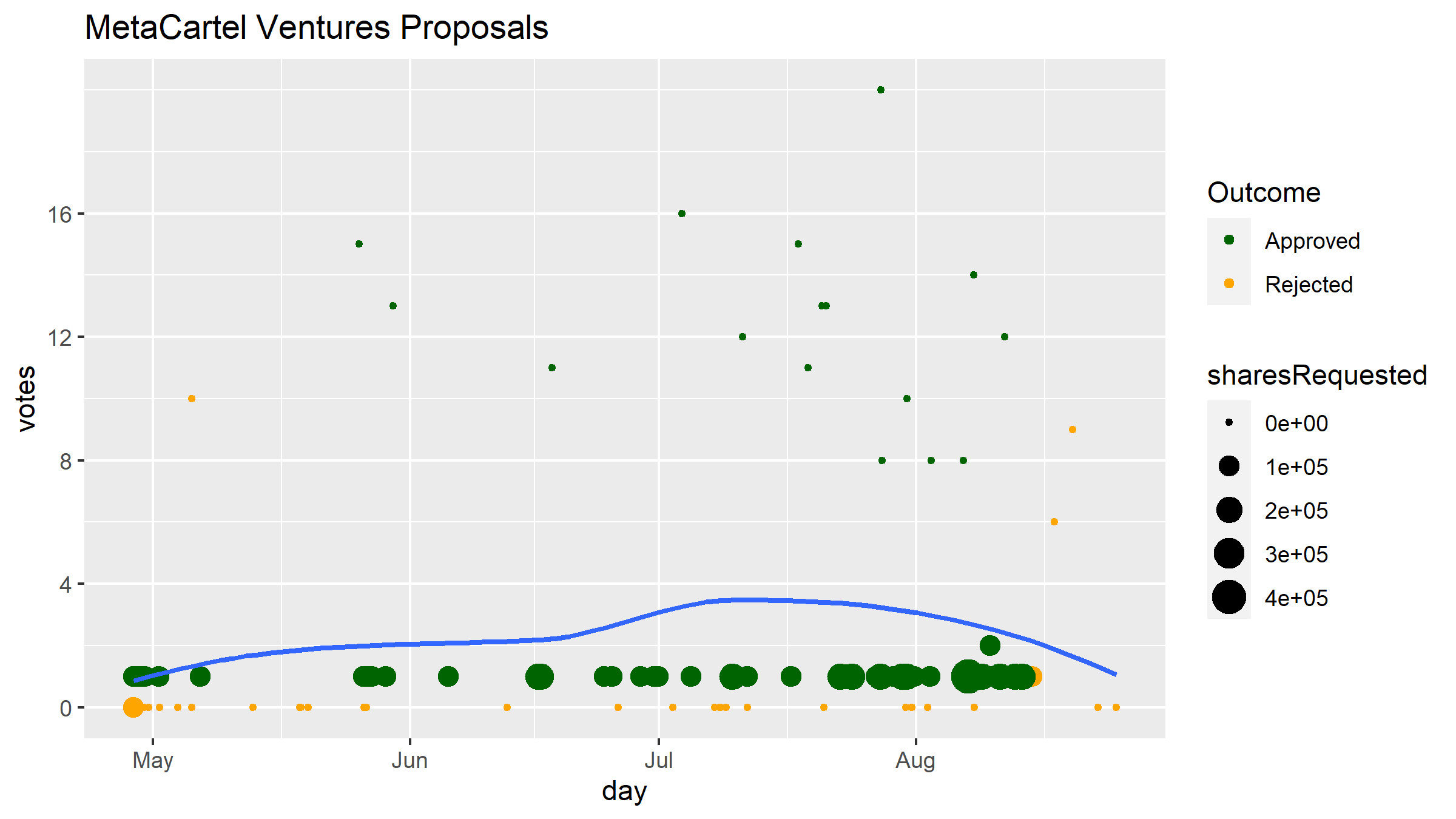

MetaCartel Ventures Proposals: Number of voters (Y axis), outcome (colour) and shares requested (size)

The Ventures DAO is sustaining a higher number of unique participants in its votes, although the maximum number to participate in a proposal is only around 18 out of the ~100 total members. In addition to proposals on investments, most of the proposals are for things like “DAO Member of the Month” and share awards, but also “Tax accounting services”.

“The LAO” is a similar idea, also based on the Moloch principle of rage quitting but with a legal entity in Delaware front and centre. The LAO is more secretive with the names for its proposals, and so less can be inferred about what the members are voting on.

The LAO Proposals: Number of voters (Y axis), outcome (colour) and shares requested (size)

The graph shows that The LAO is using the Moloch contracts differently, I assume proposals with large share requests are new members and these have been pre-approved, hence only being voted on by one member to approve them. The votes with 8-20 participants are likely about substantive matters like investments. The LAO has a total of 65 members, $3.7 AUM (Dec 20 2020), and has already spent $4.5M.

For these venture-oriented “DAO”s the entity is really just a convenient structure to use for handling funds, but secondary to the legal entity in terms of its capacity to make decisions about those funds (without getting named people into trouble). Whether these entities are successful depends on whether their members make good investment decisions, but the idea that it is a DAO that’s in charge and that people can engage in this kind of activity through a DAO is far-fetched. In the case of any major issue with these DAOs’ operation, things will proceed according to whatever is written in the legal entity’s specifications and contracts, or failing that the courts can be engaged to seek redress.

DAOstack

The DAOstack blog has been quiet in 2020 so I’m not sure what the team have been up to on development. There are a few DAOs which have continued to operate at a moderately large scale, recall that for DAOstack the mechanism for predicting and boosting proposal outcomes is a key feature, and so DAOs that scale are more immediately within DAOstack’s ambitions.

The two larges DAOstack DAOs which are active in 2020 are dxDAO and necDAO. These are encouraging for DAOstack because they show use of the DAO infrastructure by external parties who need something like this.

- necDAO is associated with DeversiFi, the exchange formerly known as Ethfinex, as it aims to transition from a centralized to decentralized mode of operation. So far the activity comprises 31 proposals that mostly concern how NecDAO should engage with DeFi products and funding for some marketing initiatives.

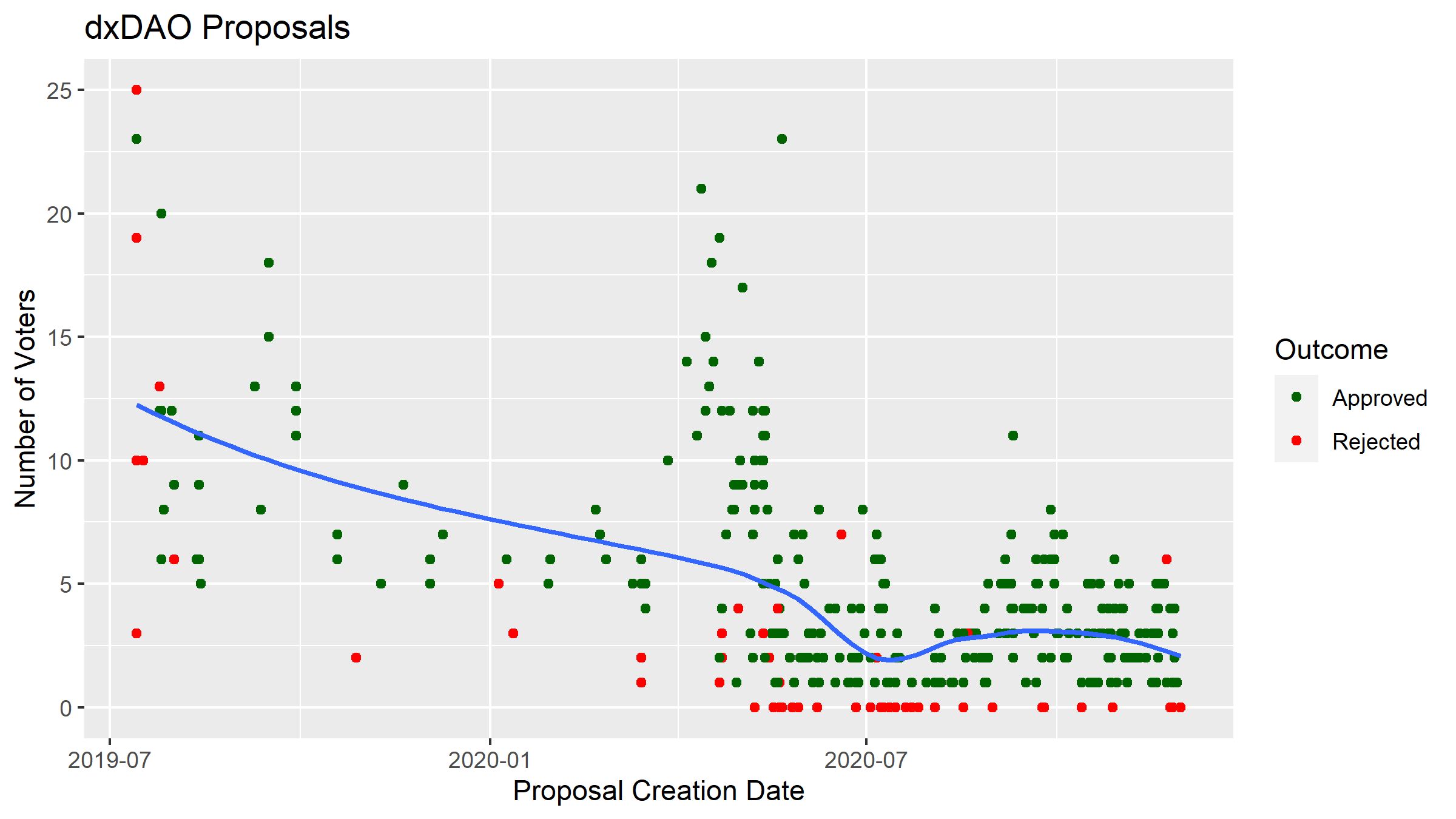

- dxDAO, for governance of a decentralized Dutch auction platform, is still going with regular proposals, although the number of people turning out to vote has diminished over time.

dxDAO Proposals: Number of voters (Y axis), outcome (colour)

Last year I looked at Genesis Alpha, which was an experiment initiated by the DAOstack team. Grace Rachmany has helpfully provided an account of its decline47 which makes for an interesting read. By Grace’s account there was a mis-match between the aims and vision of the Genesis Alpha participants and that of the DAOstack team which set up and funded Genesis. Her account of the experience makes for some interesting reading.

The DAOfest explosion is one of the great successes and great failures of the Genesis Alpha, and it resonates with some of the previous criticism of DAO funding distribution in DASH. Basically, the problem is that people love events and meetups, and they love getting paid to put on events in their local communities. They love it so much that a tremendous amount of money ends up going towards events that don’t have tangible outcomes, and even if they do, there is generally nobody accountable for maintaining the community of event organizers. The great thing about community events is that they bring in more DAO participants. The problem with community events is that they bring in more DAO participants. These new participants want to fund… more events!

- The State of the DAO: Rise, Fall, and Rise 47 by Grace Rachmany

There is also an exit letter on Google docs from two of the leaders of the Genesis DAO, these making the point about the tension between a DAO for collaboration (which the participants wanted) and one for distributing funds efficiently, with self-interested voting being for some an expected outcome and for others the thing which ruined it.

In all these materials there are also strong undertones of people joining a DAO without any strong shared idea about what it was going to be about or for. With no shared purpose it was doomed to fail.

Colony

Colony DAOs are aiming more squarely at the collaboration and coordination end of organisations. It offers flexibility in structure (hierarchical models as well as more decentralized) of how to arrange members.

After a number of people suggesting I check it out for the next version of PPCC I did finally get around to looking at the 3 DAOs listed as using Colony by DeepDAO, although most of the proposal and member stats are not working for them. I also found it difficult to locate these DAOs in the wild, which can often be the case but in Colony’s case I don’t think they are publicly viewable.

Nice example of what people might want to build with Colony, a ‘Peer Production EncyclopeDAO’

Things became more clear when a new blog post 48 appeared titled “(Re)Introducing Colony”, in which founder Jack du Rose panned his own Dapp mercilessly:

There’s no point in being coy here: our Dapp suuuucked! It was about as pleasant a user experience as root canal surgery, and not as useful.

The post goes on to announce that readers should look out for New Colony, which will be announced with launch features in a future post, road map and details of the Colony token sale to come in 2021.

Ethereum the platform

Virtually all of the DAOs and DeFi projects discussed above are running on Ethereum’s blockchain, and in 2020 it is showing signs of strain. The difficulty of syncing and maintaining an Etherum node is well known, and many Dapps don’t run their own but instead rely on Infura, a hosted solution from Consensys.

These difficulties were highlighted by an unexpected hard fork 49 which only affected a small number of nodes, but those included Infura’s and therefore caused major disruption on the network. The story behind how this came to happen also highlights a weak process for approving and deploying changes to consensus rules. A bug in consensus code was silently fixed by developers and pushed out in an update without explanation. Another vendor then discovered the bug independently, saw that it had been fixed for the majority of nodes, and decided to test in production to see what would happen - the result was un-updated nodes being forked off the network.

Meanwhile, ProgPoW was repeatedly brought up at Ethereum Core dev calls and even seemed to have the greenlight 50 after one call, but there was considerable pushback from other developers and the broader community on twitter so this won’t be happening after all.

Increased usage of the network has seen transaction fees increase considerably in 2020, to the point where the community has considered ways of increasing the block size limit again.51 Higher gas limits and other ways of increasing capacity increase the requirements placed on full nodes, and increasing these too much will cause some nodes lose touch and no longer be able to keep up with the network. Over time, these costs compound as more transactions per block add up to more blockchain state to compute.

The balance the Ethereum developers and miners are looking for is between keeping the Eth 1 network useable long enough that the transition to Eth 2 can occur before Eth 1 becomes unusable. Phase 0 of the Ethereum 2 launch began in December52, but this initial phase does not provide any smart contract functionality and is more about ensuring that PoS participants can produce blocks without breaking consensus and iron out any bugs.

Ethereum is the home of DeFi and DAOs and it’s where almost all of that activity happens, but Eth 1 is showing signs of strain and user experience is suffering. The question now is can Eth 2 get up to speed smoothly and before another smart contract platform attracts significant market share for some of the stuff that is Ethereum-dominated. This has been the case, but now more of the ETH competitors (Polkadot, Cardano, Cosmos, Tezos) are online and bringing their own smart contract features online.

I have covered Polkadot for the crypto governance research project this year too, but it is still settling in with the core blockchain functionality and people are just starting to build things with it.

Bitcoin the safe haven asset

Writing at the end of the year, when Bitcoin’s price has recently broken to a new all time high and a growing list of publicly traded companies are stating that they hold significant amounts of BTC53, it’s easy to conclude that it is becoming popular as a safe haven asset in a scenario where most national governments are engaging in unprecedented expansion of their money supply with COVID-19 bailouts of various forms.

Earlier in the year, when the USD price of Bitcoin and most other crypto-assets took a sharp 50% decline in two days in March54, this kind of outcome felt less likely. Dollars were in demand in March, but now many people are considering the scale of dollar issuance, with ~20% of all dollars being issued in 202055, and expecting inflation to kick in to some degree.

Here Bitcoin’s “store of value” proposition, marked as it is by the volatility of -30% down days, is different for people depending on where they are and which other currencies they have access to. For people in countries with rampant inflation, BTC hit a new ATH much sooner than November56, and I’m sure Bitcoin makes for a more “comfortable hold” at this stage than anything which looks like it might go the way of hyperinflation. Central banks don’t necessarily or usually operate their currencies in a way which is advantageous to the small depositor, particularly in challenging times. One of the things which cryptocurrencies offer is an escape from a badly managed local currency, into something which is run and steered differently. Bitcoin’s promise not to change the rules, particularly the rules about diminishing supply, and its mechanisms for enforcing those rules, are its most important features for many holders.

Mostly transparent public ledgers like Bitcoin’s blockchain are a solid basis upon which to issue a global reserve currency, because everyone can see that the rules are being enforced properly for all. It is also advantageous for the public, or could be, to have public institutions or other entities which have a material impact on the world, to conduct their trade on such transparent public ledgers. “Proof of Reserves” is a concept that Nic Carter makes a compelling argument for - cryptocurrency exchanges could prove that they have enough reserves to cover their liabilities, thus enhancing their reputation, by making clever use of blockchain referencing.

The same logic extends to many other types of organisation, if we want to keep it honest making it transact in cryptocurrency on a transparent public ledger makes it easier to hold that organisation to account, and makes it harder for corruption to escape detection. Furthermore, any kind of record can be anchored into a blockchain to provide assurance that it existed at a certain point in time, and when these records are woven together they can provide a high degree of assurance that a system which has been used to record information has not been tampered with. In Brazil, a company called Voto Legal provides a service which candidates in municipal and mayoral elections have used to track their campaign donations57 by anchoring these in the Decred blockchain with dcrtimestamp. Decred’s Politeia proposals site and contractor management system are built on the same principle and tooling, providing a public record of governance discussions and decisions which cannot be edited without leaving obvious signs of tampering.

However, this kind of push to use blockchains to increase organisational accountability is in its nascent stages. Instead the focus from various state and regulatory bodies has been on how to 1) read these public ledgers in a way that allows them to know who owes them taxes and when cryptocurrency comes from an illicit source, 2) ensure that the entities through which people can move funds between the fiat and crypto systems are able to identify their users. With effective KYC at entry and exit points, basic blockchain analysis skills are all that’s needed to identify most of someone’s crypto transactions.

I saw this first-hand when working on analysis of the Decred chain58 this year, a couple of well established linking heuristics are enough to map out all the addresses controlled by a wallet, unless they are taking precautions like mixing their coins. A public ledger that allows people you transact with and interested onlookers to know about your other transactions and how much of this bearer asset you have in your possession - I think it’s sensible to be cautious about how one uses that. I’m actually holding off on publishing the next parts of this research until Decred’s mixing is available to all through the Decrediton GUI wallet in the forthcoming v1.6 release.

Mixing coins makes it much more difficult for an observer to tell where the mixed coins came from, and it seems likely to me that exchanges will be (are being) pressured to avoid assets which offer effective privacy to their users. So, we seem to be heading to a situation where the rules in some places will make it difficult for people to acquire cryptocurrency that they can safely hold and use themselves directly. Once assets leave an exchange the owner can mix or shield their transactions, but it may be that the exchange effectively stops accepting mixed assets as deposits, forming a grey market for these on the side where people trade on decentralized exchanges, Over The Counter, or Person to Person.

It is my view that the transparent public ledger Bitcoin uses is fundamentally not suited to criminal use - for while it might not be possible to freeze the accounts it is possible to follow the money, the trail will never disappear, it is sitting in public view waiting for someone to recognise it, and many people are being caught out by this.

On the other hand, the easy covert storage and censorship resistant properties of Bitcoin make it more suited to humanitarian use cases where the user has the prospect of at some point in the future moving to a jurisdiction where they have a right to use Bitcoin without persecution - in which case the public ledger is less of a disincentive.

National governments themselves can avail of the censorship-resistance of Bitcoin to bypass sanctions and the payment providers who aren’t allowed to deal with them. Venezuela has gone from cracking down on Bitcoin miners to mining the asset itself59, and Iran is formulating a national strategy60 for its emerging crypto mining industry, which already accounts for 4% of global BTC hashrate according to the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index.

There have been some efforts to promote cryptocurrency adoption in places with a particular need for it, such61 as Venezuela62, but it seems that most of these have proven ineffective at stimulating a local crypto economy. However, there are signs that organic grassroots adoption is growing in Africa and Latin America (see LocalBitcoins report volume here), with a story about Nigerian protestors using Bitcoin to bypass a banking block63 garnering some attention.

Let us not forget however that Bitcoin with greater adoption is Bitcoin with high fees, which will make it less useful in many places. The Lightning Network is currently the best hope for Bitcoin to serve use cases that only work with low fees, and in addition to steady development LN revealed Lightning Pool64, a way for people to pool liquidity and offer it for a fee as a service to the network. Managing channel balances and having enough liquidity on the right side in each is one of the issues with receiving payments on LN, Lightning Pool is offering people a chance to earn some return by deploying their assets to solve this problem.

Another Brick in the Institutional Walled Garden?

Michael Saylor, CEO of MicroStrategy, a publicly listed company which has been on a Bitcoin buying spree in 202065, is one of the more interesting characters to emerge on crypto twitter this year. MicroStrategy announced in August that it was going to make Bitcoin its primary reserve currency to hedge against dollar inflation, and has since then bought 70,470 BTC, putting it one place ahead of the United States government as the fifth-largest holder of Bitcoin - although I don’t think this considers that US Gov just added to its balance with a seizure of $1 Billion worth of Silk Road era BTC.66

Saylor was quickly adopted by many Bitcoin fans as a new champion who was preaching the message of escaping inflation with fixed-supply Bitcoin within circles where people have more money at their disposal and more weight to push the Bitcoin price higher if they add demand to the market. Saylor has reciprocated with poetry and tweets singing the praises of the Bitcoin Maximalists, and echoes their talking points. With more companies announcing Bitcoin positions, this seems to be a major catalyst driving Bitcoin’s price to new highs.

Bitcoin is set up to benefit early adopters, it gives them more coins to incentivise them to get in and start promoting it. This has made it a vehicle for wealth transfer as it gains adoption. Bitcoin’s fixed supply means that if it takes off and becomes widely adopted the price will increase, the people who bought it earlier will have done so at more favourable rates and will become more wealthy than the people who bought it later. As Bitcoin makes its way onto the balance sheets of large corporations, they also become major beneficiaries of future price appreciation.

So, once the institutions are Bitcoin holders, and there’s a version of Bitcoin which suits them, where do people go for p2p electronic cash? This could still be Bitcoin, at the margins, but there are some good reasons to think it won’t be.

Exchanges won’t except BTC from certain blacklisted addresses, and many of them retain the services of chain analysis companies who can tell them about any taint associated with incoming coins - I expect that over time it will become increasingly difficult to send coins which have been mixed to an exchange. The Lightning Network could provide a solution to use Bitcoin for regular p2p transactions, but it seems likely to remain fairly exclusive while the technical barriers are high and on chain fees for opening and closing channels are expensive. The privacy implications of transacting on LN are also just being explored.67

Reasonable privacy is a prerequisite to widescale self-custody and use of cryptocurrency. If people can easily find out how much cryptocurrency you have, it’s not safe for you to have very much. In 2020 we are seeing the outline of this conflict emerging, a wall being built around “safe BTC” and the people you can get it from, with mechanisms in place that encourage leaving it in the custody of some company. This is the agenda of the people behind the new proposed regulation of transfers to “self-hosted” wallets.68

On the other side are people building around whatever points of centralization they can find, developing infrastructure to deliver their vision of a decentralized [whatever]. If Decentralized Finance can replace financial intermediaries with smart contracts and reduce costs by increasing efficiency that’s great, and doing it on an open accessible blockchain is even better. However, for me personally “decentralize finance”, in the sense of aping the fiat financial system on a blockchain, is a fairly weak rallying cry.

Decentralized Exchanges of various forms are however proving themselves to be a useful addition to the ecosystem. Ethereum users have a variety of liquid decentralized exchange protocols with automated market makers to choose from now, and Decred has recently launched the initial version of DCRDEX, which is running on a client-server model for accessing order books, with traders then completing the trades directly on chain and the server standing by to ensure everyone follows the rules about following through with matched orders.

Using DCRDEX at this Minimal Viable Product stage is a fairly interesting experience69, as it requires some command line node and wallet tools to be running to successfully make orders and execute trades - it also requires the user to have synced both the chain they are sending and receiving on. This is quite a unique take on the decentralized exchange concept, because the DEX itself is operating more like an old bulletin board site, email or game server, relaying messages about what’s available to trade and then sending the signal when a match is made, at which point the traders engage in a back-and-forth exchange on chain, each revealing their part of a secret in turn that allows the other to claim the newly acquired asset.

I had fun learning to do clay animations and video editing during a lockdown, this is a still from a forthcoming DCRDEX music video.

Custody is Critical

Self-custody of cryptoassets is in my view their most challenging aspect, a key hurdle to real adoption. Without the right kind of custody, for example if most of a a cryptoasset’s supply ends up sitting in random exchanges selected by undiscerning holders, it becomes more open to weaknesses like fractional reserve banking - where an exchange doesn’t actually hold the assets to back all the deposits on its books. For networks with Proof of Stake consensus or binding token-holder governance, the situation is even more serious if balances held by exchanges can be mobilized to affect the outcomes of decisions about the project.

People who leave cryptoassets in the custody of exchanges are exposed to the chance that their assets can be lost (e.g. through hack or malfeasance), but then again people who self-custody their assets are also exposed to risks. The risks are different and much depends on whether one has the technical skills to understand and manage them.

The level of difficulty involved in understanding cryptocurrency and how to handle it safely is still, writing at the end of 2020, pretty high. I would guess that most people in the general population still find it hard to understand how this stuff works conceptually, it’s not easy to learn how to make wallets and transactions, and doing so safely requires reasonably advanced computer security know-how and/or specialized hardware.

To illustrate the variety of pitfalls here, Ledger kept a database with the addresses and contact details of the people who bought their cryptoasset security products, then allowed those details to be hacked, sold and ultimately dumped publicly70. This is damaging for every affected customer because it opens them up to phishing attacks but also more targeted attacks, where the attacker knows what method their target is using to protect their funds, and the address where they have their orders delivered!